What is the opposite of being motivated to succeed?

Well, it must be lack of motivation.

Or not caring.

Because surely nobody is motivated to do poorly.

Or are they?

A study published in the Journal of Educational Psychology shows that in fact some students purposefully behave in ways that will lead them to fail.

They are motivated to fail.

According to the study, some students disengage from school activities, skip classes, procrastinate studying. Or, maybe don’t study or go to school at all. Not because they don’t take their performance seriously. But because they take it so seriously they have a deep fear of failure.

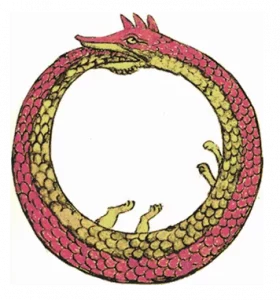

A student failing because they’re afraid of failure. It sounds like one of those hopelessly absurd situations. A catch-22. Or a snake trying to eat its own tail kind of a thing.

How could this be?

We all pretty much agree that if you succeed without putting much effort into something then it must mean you have talent. It follows that if you do put real effort into something and fail, then you lack ability.

Suppose you’re afraid that you lack ability. Then the best way to avoid confirming that suspicion is to never put effort in. That way, at least you can preserve some of your self-worth. Now, you’re motivated to fail.

Student Motivation and Engagement

Krista De Castella and Don Byrne from the Australian National University along with Martin Covington from the University of California, Berkeley studied more than 2000 students in Japan and Australia and made radical discoveries about the relationship between student motivation and engagement. They published their paper in the Journal of Educational Psychology.

The researchers gave the participating students a set of questionnaires asking them about their achievement goals and how they felt about failure. For example, they were asked to rate how important it was for them to do better than others (achievement goal), and how much they worried about what others would think of them if they failed (student fear of failure).

The researchers then correlated the answers on these questionnaires with the extent to which students’ applied strategies to actively preserve their self-worth. They used questionnaires that assessed three strategies: defensive pessimism, helplessness, and self-handicapping.

- With defensive pessimism, a student sets unrealistically low expectations for themselves on tasks where their performance will be evaluated. This helps them change the meaning of failure. If they do better than the low benchmark they set, they feel pleasantly surprised.

- With helplessness a student adopts the belief that their academic performance is outside their own control. If they do poorly, well, it’s not their fault.

- With self-handicapping a student actively engages in behaviors that can later be used to excuse poor performance. Like, leaving studying to the night before a test. If they don’t do well, it’s because they didn’t spend much time studying.

So, what were the ways the differently motivated students approached success and failure?

Motivated to Self-Defend

De Castella and her colleagues found that many of the students had a fear of failure. Even some students who were highly motivated to succeed. But, in these students fear did not weaken performance. On the contrary, their strategy for avoiding failure was to try harder to succeed, employing more effective study skills to help them along.

The surprising finding was that some students were motivated to fail. These students were afraid of failure but weren’t particularly motivated to succeed. And they performed worse in school than students who didn’t care whether they succeeded or failed.

The students who were motivated to fail had the worst academic performance. And they were the most likely to engage in defensive strategies.

Ironically, in the study these students were also the most likely to say they “couldn’t care less” about school. They did care. They were protecting themselves from failure.

We all feel a fear of failure – at least now and then. De Castella argues that being motivated to succeed insulates you from the negative effects of fear.

De Castella’s findings, which held true for both the Japanese and Australian students, run counter to the traditional view of achievement where rock bottom is when you have accepted failure as an outcome.

It’s worse when you think you can’t do it. But you don’t want to know for sure. So you make sure not to try. You handicap yourself. And you tell everyone you don’t care.

A Recipe for Overcoming Student Fear of Failure

So, what does the path to success look like for students who obviously care (even if they say they don’t). But who impede their own achievement because of their fear?

De Castella warns that increasing the pressure on students who appear to be disengaged is not productive. This may instead add fuel to the fire by intensifying the student fear of failure. Added pressure can make these students even more motivated to fail.

The two things that trip these students up are lack of confidence in their own ability combined with few reasons to really want to succeed.

A recipe for increasing confidence and the desire to succeed includes:

- Reinforce the belief that ability and intelligence grow with effort

- Replace the self-handicapping, defensive strategies with practical and effective study skills for attacking fearsome content areas

- Provide some motivating reasons to want to learn more, regardless of grades received

Nurturing student motivations is a long term commitment. Change won’t happen overnight.

The first step is to figure out where they are now. Do they really not care at all?

Or are they actually motivated to fail?

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

very insightful thought.

My 15 year old son gets decent grades when I ask about his school work every day, but when I leave him on his own he gets subpar results. I don’t want to have to check his work every day at some point this has to be important to him. He wants to be a student athlete so he has to maintain a certain gp

It’s good that he has long-term goals, and that he does the work (with encouragement). Much better than being “motivated to fail.” You can build on his future plans by talking through what majors fit with the student athlete. And how his current schoolwork helps him get ready to succeed in those majors. Seeing the concrete value of what he’s learning helps improve motivation.

Wow, it’s powerful to have my own approach to learning put into words. All my life I’ve engaged in both self-handicapping and defensive pessimism behaviours. I’m now 29 and, suffice it to say, have nothing to show for my potential. Oh well, c’est la vie eh?

Thanks for sharing, David. It’s never too late to begin to turn things around 🙂