Seasoned globetrotters are able to adapt to new cultures efficiently. It’s not easy to do so. Learning to function within a new culture can be hard. Given the mass of potentially relevant information to try to digest, you might be tempted to give up before getting started. Yet, you can build your cultural competence.

There are many types of information that may help you understand people from another culture better. Possibilities include learning something about the region in which the culture resides, its economy, political system, social systems, belief systems, religion, languages, and so on.

There are also lots of different academic theories about what makes cultures different and similar. Or, you could study the rules or norms that appear to govern how people from certain cultures behave.

Because ‘culture’ comprises a vast learning space, getting up to speed can be overwhelming without some way to scope the problem. Folks who are cross-culturally competent do this intuitively.

Louise Rasmussen and Winston Sieck of Global Cognition conducted a series of studies to better understand how real-world, global professionals cope with this challenge. As part of their studies into what makes some people cross-culturally competent, they interviewed nearly 150 individuals with varying levels of cross-cultural experience.

The sample of professionals ranged from novices who had never traveled abroad to “cross-cultural experts.” The experts were seasoned globetrotters who had completed numerous, lengthy overseas assignments that required them to interact extensively with several different local populations.

The researchers found that these seasoned globetrotters, as compared with novices, share a key insight about how to manage their learning:

What one should know, how much, and where one should start depends on how the cultural knowledge is going to be used.

With the practical goal in mind, knowing a few types of information that can be immediately useful allows the cross-culturally competent to reduce the amount of new material they have to contend with to a manageable size. This, in turn, improves their ability to sustain the motivation to keep learning about new cultures.

The ways in which these seasoned globetrotters use cultural knowledge to some extent depends on the nature of their tasks. But it also depends on their personal style. Personal style means the strategies they feel most comfortable using in order to achieve social objectives.

Some cross-cultural experts like to use humor, some prefer to demonstrate that they are competent, some strive to build personal, meaningful relationships, some combine these approaches, and yet others tailor their approach to each situation.

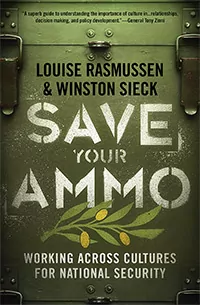

Rasmussen and Sieck published these findings as a chapter, Metacognitive Underpinnings of Cross-Cultural Competence Development, which appears in the book, “Advances in Design for Cross-Cultural Activities.” Dr. Rasmussen presented the findings at the 2nd Cross-Cultural Decision Making Conference held in San Francisco, July 2012.

Regardless of their preferred social strategies, cross-culturally competent experts know what the categories of knowledge are that are useful for them to learn. This means that the cross-culturally competent understand what the types of cultural knowledge are that can support their preferred strategies for achieving objectives.

Sometimes the categories of information they find useful coincide with formal or academic categories of cultural information, such as for example family structures, power, and status.

Often they instead rely on more practical kinds of knowledge. Their categories often have labels that immediately disclose the intended application, such as for example social lubrication and call-your-bluff information.

Social lubrication cultural information can be used to ease tensions in stressed situations. Call-your-bluff information can assist in determining where a person from another culture stands on important issues, and may help establish whether or not that individual can be trusted.

Understanding the types of information that support their personal strategies allow seasoned globetrotters to engage in everyday learning and ongoing acquisition of cultural information. And it also allows them to scope the culture learning space appropriately to the time constraints they are operating under.

Because they know what they need to learn, seasoned globetrotters do not have to spend time cramming in everything they can about a new culture. Instead they can focus on the information that helps them accomplish their objectives. Having this focus prevents them from getting overwhelmed. It helps them muster the motivation to start over each time they find they need to begin learning another new culture.

Image credit: Hjl