You never used to hear anyone say the word cognition. More and more, it seems to crop up in all kinds of places.

I see cognition crop up in newspapers, magazines, and letters from my kid’s school. As someone who makes his living off of cognition, that’s comforting.

But what is cognition really about?

Is it doing anything for us besides offering another fancy word to bandy about?

Cognition is about how the mind does amazing things like:

- Recognize that a flying object is a goose

- Understand a paragraph or poem

- Remember a new friend’s name

- Play chess

- Come up with a bright idea

In short, cognition refers to the ways the mind goes about perceiving, remembering and thinking.

The science of cognition is a branch of psychology. As far as sciences go, it hasn’t been around all that long. Cognition really took hold as a serious science in the 1950’s. It sprung up and started advancing rapidly, right along with some of its partner sciences, such as computer science, neuroscience, and linguistics.

Cognitive psychologists are fond of talking about a cognitive revolution that occurred around that time. One of the leaders of that revolution, George Miller, wrote a nice essay reflecting back on his experience in those early years. His take on the cognitive revolution, published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, serves as my primary reference. My favorite book on the topic is Howard Gardner’s, The Mind’s New Science.

The revolution started because psychologists weren’t allowed to use the word “mind.” At the time, experimental psychologists wanted psychology to be more objective. They did this by focusing on what they could all see. Behavior can be witnessed first-hand. Stuff happening in the mind could not. It was out of bounds.

The rigid focus on behavior led to some interesting gymnastics of jargon. You couldn’t say language in professional circles, for example. Instead, the scientific term was verbal behavior. You couldn’t talk about memory, because that was inside the mind, so you had to restrict yourself to discussing learning. Intelligence was interesting, because it sure sounds like something on the inside. The way around this was to define intelligence as what an IQ test measures. You could see that.

Psychologists actually learned a lot by stripping down their theories, and focusing on what they could objectively measure. One thing they learned was that they really did need more than behavior to explain human psychology. Miller put it like this:

As Chomsky remarked, defining psychology as the science of behavior was like defining physics as the science of meter reading.

It started to become clear that to really get anywhere, psychological scientists would have to think about how the mind works. They would need to use some theory about the mind to explain the behavioral data. But, they didn’t want to go back to old words that had been used before Behaviorism came along. They needed a new word.

The word that won out was cognition.

Cognitive psychologists came into being, who, according to Miller, were “unafraid of words like mind and expectation and perception and memory.” A flurry of fascinating cognitive research began to emerge by the mid 50’s. Two quick examples were:

- George Miller published what may be the most famous result from cognitive psychology, The magical number seven, plus or minus two. The “magic number” has often been taken as the span of short-term memory.

- A Study of Thinking, by Jerry Bruner, Jackie Goodenough and George Austin took seriously the notion of cognitive strategies, which brings intention into the mix.

Theory May be Fun, but has Cognition Done Anything Useful?

In the 1970’s, cognitive psychology was ready to start tackling practical problems. For example, it started to take on problems in education. This was a way for the science of cognition to show what it could do. It was also a way for cognitive psychologists to test and improve their theories with more realistic problems. Richard Mayer’s essay on cognition and instruction, published in Educational Psychologist, provides the basis for my remarks here.

As Mayer points out, problems in education are often addressed by, “well-intended fads, expert opinions, and doctrine-based agendas.” This hinders the progress of educational practice. What’s needed are instructional techniques based on research evidence and tested theory. Cognitive psychology helps with this. Mayer describes two general areas in which cognition has contributed to education:

- Cognition of Core Subjects

- Teaching of Cognitive Strategies and Cognitive Skills

What is Cognition of Core Subjects?

Cognitive psychologists have helped identify specific concepts and skills needed for subject areas. These include reading, math, science, and history. A quick example for math is figuring out the precise knowledge needed to learn how to add and subtract two numbers. One aspect that cognitive psychologists have examined is “number sense.” Number sense means that a person has the concept of a number line and skill to use it. It can be tested by asking questions like “Is 6 or 2 closer to 5?”

Mayer describes evidence that having the mental number line down is related to learning arithmetic. Cognitive research with 6-year old children first showed that those who knew the number line could learn simple arithmetic fairly easily. Those without number sense had much more trouble. It’s been estimated that half the entering students don’t have it.

In a next step, cognitive researchers tried training kids on the mental number line. They used various games, such as comparing two dice to see which number is higher. They tested their ideas by comparing to a control group who did not receive the training. By end of the year, twice as many of trained students mastered basic arithmetic as did students in the control. The evidence showed the training to improve number sense was effective.

This is but one example. Cognitive psychologists have conducted myriad studies that contribute to learning specific subjects in school.

What are Cognitive Strategies?

Cognitive strategies are ways the learner intentionally influences learning and cognition. Examples include study skills, such as strategies to improve reading comprehension. They also include thinking skills, such as strategies for evaluating sources on the web.

Lots of research has yielded evidence attesting to the effectiveness of a number of cognitive strategies. Mayer points out that work on cognitive skills and strategies represents a paramount contribution of cognition applied to education. With a solid research base built over the past several decades, we can now improve how students learn and think by helping them cultivate and use cognitive strategies.

Improving our understanding of the cognition underlying specific subjects, and of the cognitive strategies people use to tackle challenging mental work are just two ways cognition has aided education so far.

Other areas of improvement include new ways of assessing learning outcomes, new ways of thinking about intellectual ability (well beyond what IQ tests measure), and new ways of using computers for instruction.

At Global Cognition, we’ve been exploring cognition “in the wild” to support the development of complex skills that are still poorly understood. For example, we are working to understand and improve the cognitive strategies people use to adapt to new cultures.

Cognition has also made contributions in numerous other fields, such as medical practice, jury decision-making in law, , marketing, voter behavior in politics, the design of airplane cockpits and the dashboard in your car, making computers that anyone can use (and ones that can think for themselves).

And the list goes on.

There’s a good bet that’s why the word is becoming increasingly popular and widely used.

The science of psychology has advanced dramatically in the last several decades, propelled forward by the cognitive revolution. Now is the time to put more of that good theory into practice.

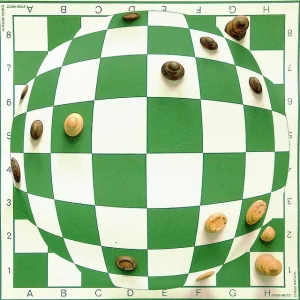

Image Credit: fdecomite

References

Here are some of the problem with a cognition agenda:

– It fits our subjective experiences and pop ideology/beliefs/natural language too closely to likely mean much.

– If it’s important – we would find it in other species – like consciousness. They either get along without it just fine or any definition of cognition that includes other animals would be very different from what cognitive scientists study.

– Why should our subjective experiences and self-reports of brain function be anymore accurate than those of the spleen?

– Growing evidence that our brains and bodies do stuff long before anything like cognition happens – http://wp.me/p167Bf-5rH

I was initially worried that a backgrounder post on “cognition” might be a bit boring. Thanks for this comment! One example of an aspect of cognitive theory is the concept of “sensory memory.” The standard take on this from a cognitive perspective includes that sensory memory deals with far more information than our conscious, subjective experience would suggest, and that it happens before more deliberative processing kicks in. It took some very clever experiments to work out the properties of sensory memory, and could not have been accomplished with mere introspection. Conscious functioning is but one aspect of cognition. A fair amount of cognitive-neuroscience research has helped further confirm a number of theoretical constructs from cognition, and enjoyed some success mapping cognitive functions to brain regions. There is a lot of current research activity at the intersection of cognition and neuroscience to the mutual benefit of the two disciplines. Comparative cognition across species is fascinating, reporting in journals like, “Animal Cognition,” that might be of interest.

It is interesting to see how cognitive changes happen in our lives all the time. For example, as we grow up and become more advanced with schooling we obviously have intellectual changes that happen and we have to study and remember things. Not to mention critically think. It is more interesting for me though to think about how our cognition changes as we get older. According to K. Warner Schaie’s findings our cognitive abilities remain stable until around the age of 60. Even such measures of vocabulary remain till around the age of 90. It is interesting to think about because most would consider prime intelligence around the ages of 20-40 because that is when people are still in college and working and increasing learning abilities. This is encouraging in such aspects like the advances in the medical field like mentioned above. We can keep learning and our cognition will only get better creating greater advances for us in the future.

Thanks, Heather. The cognitive changes during early development and later in life are fascinating. Agree with you that aging is a mixed bag, and not a simple matter of decline. With later aging, some aspects of cognition, like working memory span do tend to decline, whereas knowledge, such as reflected in vocabulary test performance, continue to increase-as you say. As people get older, they experience more distraction. However, a recent study suggests that the distraction helps to support memory. If an older adult needs to remember something new, they are more likely to notice cues in their surroundings that will help them remember it.

Everyday we experience cognitive changes whether we like it or not. As we get older and mature it impacts our cognitive changes drastically. According to Piagets theory, children progress through four stages, each stage progressing their cognitive abilities and marks a shift in how they think and understand the world. He also states in his theory, as a child develops and matures, he/she does not simply acquire more information. Rather he/she develops a new understanding of the world in each progressive stage. This is a very interesting topic and im glad to come across it.

Thanks Brenden. Always enjoyed Piaget’s work.